Sean Thielen-Esparza and the analog revival

Sean Thielen is bringing back the Sony Minidisc, but why?

In the ’90s, the internet emerged with a promise of freedom—a utopia of infinite information and instant gratification at our fingertips. Adoption surged, and we eagerly embraced the idea of detaching from our mortal coil and plugging straight into the hive mind.

Technology reflected this shift, particularly in the following decade: year after year, cameras, music players, and more folded into the six-inch glass bricks that form extensions of ourselves.

But progress, it turns out, isn’t always linear. From wired earphones to neo-Walkmans, a collective desire for purpose-built devices and tactility seems to be quietly bubbling anew. But to what end? Is there something truly better about having devices that only do "one thing," or are we just nostalgic for a past we can’t go back to?

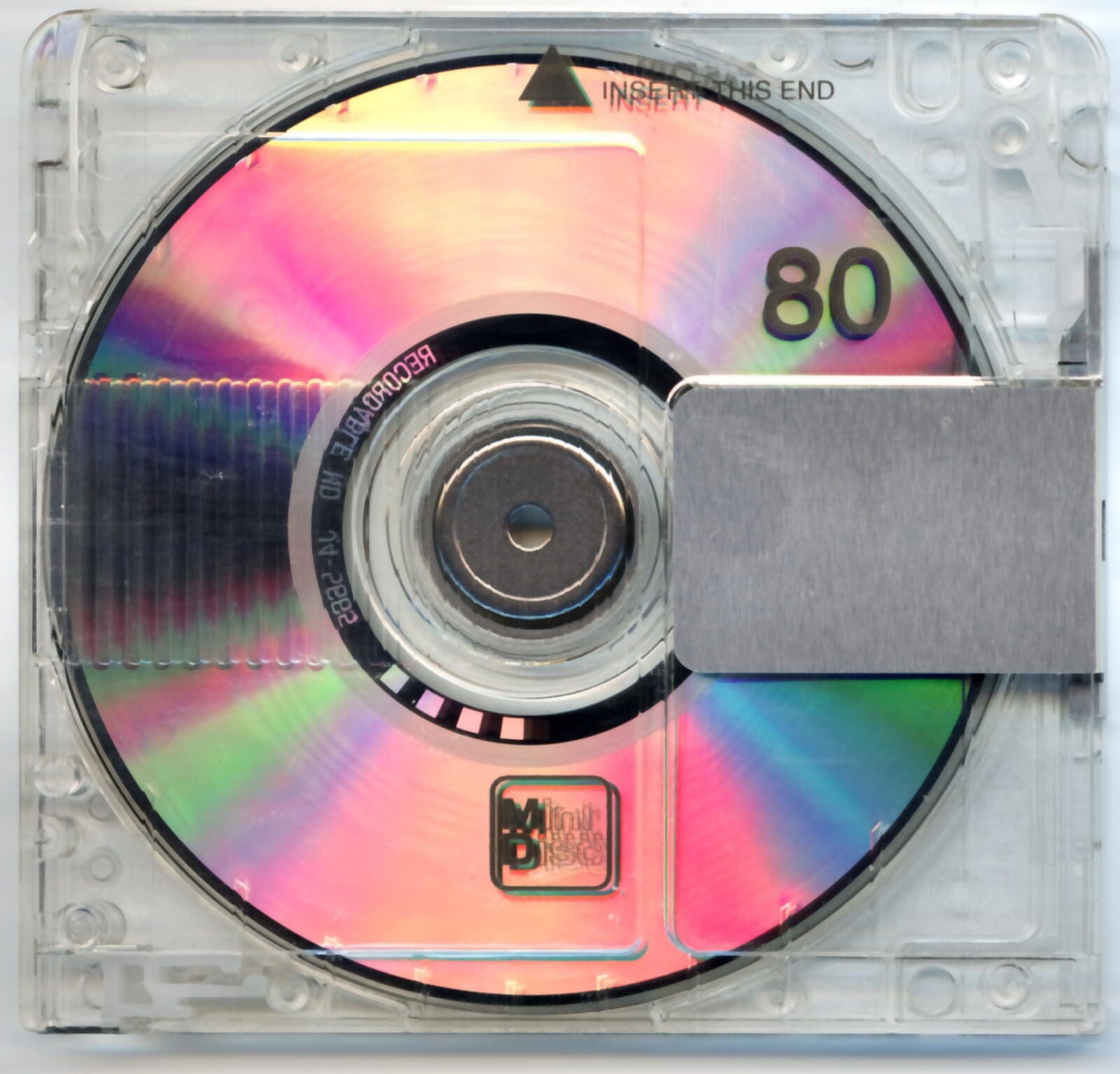

Sean Thielen-Esparza is a technologist and designer seeking answers to these questions. Titled Unfinished, Sean is embarking on a revival of Sony’s MiniDisc through a limited-run activation, reimagining the MiniDisc as a medium for artists and their supporters to exchange artefacts of projects in progress. (All a bit spy-like, if you ask me.) In November, I caught up with Sean to explore the analog revival and where he sees it heading.

You’ve had quite a diverse career—designing a crypto wallet, building furniture, and even training to become a doctor. Can you walk us through the intellectual thread that ties it all together?

I studied genetics and architecture, so when I refer to "spatial design" in my work, I mean both architecture and interior design. My genetics program was a mix of sociology and biology. Specifically, I studied ancestry and race, investigating how to take biological “facts” in genetics and make social meaning out of them—like understanding someone’s ancestry, behavior, or societal views toward them.

My excitement in tech came from products like 23andMe, which essentially claim to take “facts” about you and draw conclusions you can use to make health or ancestry decisions. For example, 23andMe might say, “Based on your genetic information, you have a particular risk of breast cancer.” To tell someone something that significant based on a lossy set of statistics and correlations is a deeply meaningful product decision.

That isn’t just “Your horoscope says you’ll be happier today!” It’s about how products take foundational data and present it as fact. People treat interfaces as truth, especially genetic data, and I became fascinated with how consumers relate to science in direct-to-consumer, well-designed UIs.

Separately, while I was in college, I worked for Apple doing visual merchandising. I learned about their ethos in presenting products and the materials they use in their stores. I helped construct furniture and launch iPhones, which taught me a lot about tech in a spatial sense.

When I was about to start medical school, I had a “come to Jesus” moment after a pretty scary run-in with cancer. It forced me to think about whether I wanted to delay my career for eight years with medical school or take what I’d learned about technology, spatial design, and truth-seeking and start my career.

So I joined a startup as one of their earliest product managers. By the time I left two years later, the company had doubled in size, and I was a PM in AI. I got lucky—it was a rocket ship in a field that ended up becoming very hot.

Where did your interest in tangible, physical objects come from?

For context, my mom is a landscape architect. My first design education was in spatial design. I grew up in LA, where my mom designed a few parks that I spent time in as a kid. She’d walk me through the park and explain things, like how she put sweeter-smelling trees in one spot so people would pause, or spikier plants like aloe in another to make passersby speed up. It was fascinating to see how spatial interventions could create behavioral change.

I also helped her with home projects, so I’ve been building things with my hands since I was little.

As for furniture and interiors—growing up in LA public schools, they looked awful, like prisons. But my mom would take me to museums and botanical gardens, environments that literally felt better in my body. I started wondering if well-designed spaces could impact my genome or health outcomes, which is why I studied spatial design alongside genetics.

In your FWB Fest 2024 talk, "The Analog Revival," you discussed how product design intersects with personal expression—especially in wearable tech. Can you elaborate?

For most of my childhood and early adulthood, I was a model. I did e-commerce modelling, and I was always curious about the brands I was cast for. As a kid, it was Disney, Kodak, toy shops. As I got older, it shifted.

I have an effeminate face, so even though I’m a straight guy, I’d often get cast alongside an entirely gay demographic. Eckhaus Latta, Paloma Wool—it was very LA, very gay, and I was the only straight guy in the room constantly.

I bring this up because people probably read me as gay based on my appearance, what I was wearing, and how I was acting. It was like a performance, all tied to the garments I was adorned with.

That’s the logic of fashion. When you wear a Supreme box-logo hoodie, you look like a hypebeast. It’s branding yourself, literally. Objects tell stories. For instance, wearing Willy Chavarria or Eckhaus Latta might read as “gay Lower East Side.”

The objects you wear—whether wired earphones or AirPods—say something about the tribes you belong to, the belief systems you hold, and how you identify with a group.

Why do you think analog is making a comeback? On one hand we’re hurtling towards an AI native future. On the other hand, we have this strong wish to unplug. Who will win out?

It’s hard to say for sure, but I think the frustration with digital oversaturation is reaching a breaking point. People want to fix their phone addiction, but it won’t happen through moralizing. The solution lies in purpose-driven products.

Meta’s AR glasses are a great example. They’re not trying to replace your smartphone—they’re an auxiliary product. But over time, they might earn the right to be more than that. That’s the key: offering something useful without overstepping.

Glasses might not be the ultimate form factor, but Meta nailed the positioning. That’s the kind of thoughtfulness we need.

Why do you think wearable tech has failed at actually being wearable?

Adornment, signaling, and identity construction in fashion are the same as in technology, but the tech industry doesn’t understand this.

Objects embody value systems, which people use to identify themselves. Are you a Meta Quest person or a Vision Pro person? Do you have a modded Nintendo Switch that signals you’re DIY, or a little Herman Miller thing that signals something else?

Tech needs to learn that identity construction draws from fashion and outfit design. There’s a huge opportunity for people who sit at the intersection of both worlds and understand them deeply.

The MiniDisc Project documents the “In-Between” states of Art. Can you tell us more?

The MiniDisc project is part of Unfinished, a brand I started three years ago. The idea came from being surrounded by artists creating incredible work but having no place to show it. I started curating shows for my friends to display their works in progress.

The inspiration came from Brian Eno’s essay in A Year with Swollen Appendices. He argues there’s no such thing as truly finished work—it’s either stripped down to its essence or abandoned out of frustration.

So I asked, “What if we showcased every version of a project, from inception to final artifact? What if we celebrated the evolution of the work instead of just the final version?”

This idea turned into pop-up exhibits. I curated a friend’s 3D-printed shoe project years before Zellerfeld, a 360-photo experience of Dimes Square, my USB Club work, and more. One exhibit, held in an empty room, drew 400 people to see my friends’ unfinished projects.

MiniDiscs are a way of documenting these in-between states. Each disc comes with an access code that lets people explore the project files and behind-the-scenes content.

Why did you choose MiniDiscs as the medium for this project?

They’re just undeniably cool. A MiniDisc is a self-evidently compelling object—it looks sick. Using MiniDiscs creates a physical excuse for people to talk about supporting artists. It highlights the idea that art exists in the touch-points before it’s “complete. It’s also a test of my theory: can you create objects that embody values and give people a way to present those values in their homes? The discs are engraved, customised, and handmade in my studio. Owning one signals you were part of a limited group supporting an artist’s work.

In a way, they’re like trading cards for my friends’ projects.

What Are You Hoping to Learn From the MiniDisc Project?

I want to see how far people are willing to go for handmade, limited-edition objects. What’s the price ceiling? I'm also curious if people will collect these like trading cards and use them to express their identities.

Follow Sean

www.seanxthielen.com

@seanxthielen

wonderful work. can't agree more with that one: "Tech needs to learn that identity construction draws from fashion and outfit design"